Friday, December 22, 2006

Monday, December 18, 2006

Monday, December 11, 2006

Monday, November 20, 2006

You may just pass by it and never notice that it’s there, unless the “Joes Shoe Repair from Union St/7th Ave” sing is placed on the sidewalk. But the wooden sign, black and red letters on a white board, is so old and weathered that you might easily miss it.

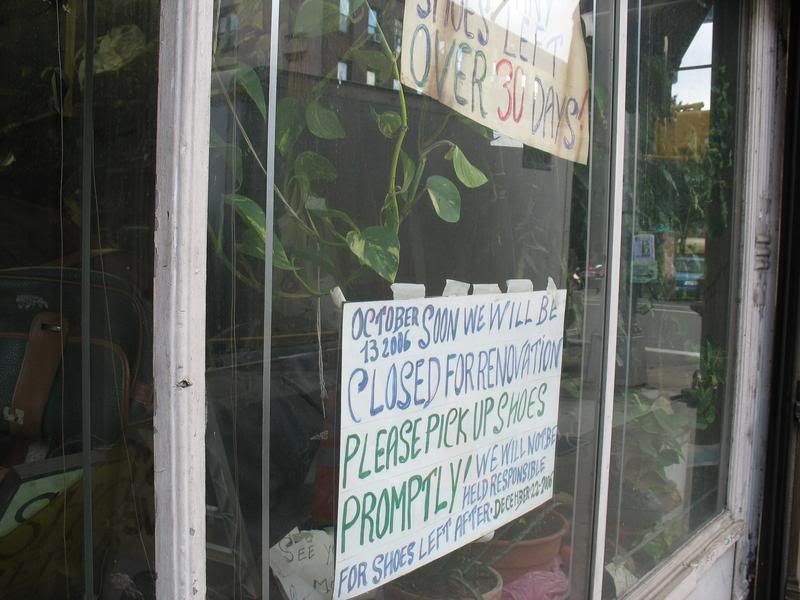

Next to an upscale French restaurant, across the street from a Natural Market on the busily gentrifying 5th Avenue in Park Slope, Joe’s store is like something somebody forgot here from the olden days. The store window’s glass is dirty. The window itself is full of randomly tossed shoes and leather coats. Two signs made on a white paper with three different color crayons are glued on glass: “October 13 2006, Soon we will be closed for renovation. Please pick up shoes promptly.” And: “We will not be held responsible for shoes left after December 22 2006. You must pick up any shoes left over 30 days!” Two plants are hanging from the ceiling, taking over the upper part of the window.

“I like to take it easy. It’s too busy here,” Joe said inside the miniscule store, where, if he wanted to spread his arms, he would almost reach wall-to-wall. But the walls are not visible, because they are covered with shelves and the shelves have mountains of shoes, sneakers, boots and sandals on them. Old sanding machines remind the guest that there is actually work taking place here. Dust covers everything. Its height determines how long nobody touched an object. A narrow path is kept free on the floor for Joe to walk around. The distinctive smell is of old leather.

The L-shaped counter right behind the door holds an ancient metal cash machine, the kind where a $ sign and a number jump up when a key is stricken. It does not give a receipt. Next is a small space on which customers can put the shoes-to-be-repaired. Around the corner is an area blocked by a white plaster panel behind which Joe works.

Across from the counter, a radiator heats up the room quickly, and above it, the wall is covered with souvenirs: A big, framed picture of Jesus Christ. In the corners of the frame is a picture of Joe’s two grandchildren, a girl and a boy; a picture of St. Giovanni; and a picture of Joe on his son’s motorbike. Next is a big wooden frame with a picture of a town in Sicily. Below is a picture of Joe with a group of kids in front of his store.

“It was about eight or ten years ago,” Joe said with a wide gesture of his left hand, while his right was holding a black leather boot. “They wanted to see what I am doing,” Joe said, obviously unimpressed.

Joe is one of the last of his kind. The cobblers, the picture framers, small appliance repair places, barbers, print shops and other one person neighborhood business are leaving the area and are being replaced by restaurants, French pastry shops, fancy coffee shops and upscale clothing stores. In the Park Slope area, Joe and another shoe repair store run by an Asian couple are the last two left.

A man in his 60s, Joe is short, with all white hair and a flirtatious smile. He moved to New York as a young man from Italy and never learned English well.

“I came and did this and that and then someone called me to help with shoe repairs. I did a little bit at the beginning. Then more. And then I took over the store. This was on 7th Avenue. Later, one guy bought half the block and started renovating. When my lease was up, he wanted $1,200 a month and offered me a 3 year lease. This was 18 years ago. I paid $500 before. So I moved here. This was cheap” Joe said while nailing a new heel on a black boot.

A store front rental on 7th Avenue nowadays goes for around $3000. No small business can survive with a rent this high.

5th Avenue started changing about 5 years ago, when many new restaurants opened and received good reviews in local and city papers. The avenue got a new asphalt coat. Dozens of luxury coop and condo houses were built during the recent real estate boom and new, wealthier occupants moved in. They too needed someone to fix their shoes. Joe had no complaints about not having enough costumers.

When he was done with a repair, Joe put the shoe somewhere on a shelf. Some of the shoes had little pink slips attached to them, but he did not put the shoes in any particular order.

A woman in her 40s came in. She had a pink slip. “This is my third time here,” she whispered to me while Joe was looking for her shoes. “He can’t remember anything. I left three pairs here and he couldn’t find them.”

Together, Joe and the woman finally located all three pairs and Joe added up on the old cash machine that she owed him $30. “You are lucky I don’t charge you for the times I came here in vain,” she said to him. “$30 even,” he replied and did not seem to notice that the woman was annoyed.

“They will now renovate this building,” Joe said after the woman left. “If they want a lot more money for rent, I will not take it.”

“I don’t know what I will do. I will retire,” he added. His sons don’t want to take over the business. One of them is a police officer and the other has a college degree. Once his nephew wanted to learn the trade and maybe take over the business, but Joe was the one discouraging him.

“I said, ‘Go do something better. There is no big money in this business. It’s lots of work. Many hours,” Joe explained. “If I have to close, I close. I don’t care. But I can’t stay home. What will I do?” he asked with a mischievous smile.

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Saturday, November 11, 2006

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Monday, November 06, 2006

Marcia Bodenstein, a 56 year-old entrepreneur from

Bodenstein, who grew up in an orthodox Jewish household, in which on Saturdays lights were not switched on and the kitchen was kosher, was used to synagogues where women and men were separated, and people were obliged to buy tickets for High Holy Days, feared God and were isolated. She was 15 when she discovered ham sandwiches and pizza. As an adult, she never went to her old synagogue, except with her widowed father, but kept searching for a more progressive congregation. After finding one that she liked in

At this Kol Nidre service, Bodenstein was surprised to see a woman standing on the podium as a rabbi. Moreover, the cantor was a woman too and the rabbi spoke English. The church was filled with people of all colors and socio-economic backgrounds. There were families with children, singles, straight and gay couples, lesbians, gay men, young and old. As a widow, Bodenstein felt at ease.

About 700 people came for the service that day with Bodenstein, organized by the progressive Jewish congregation in the upscale Park Slope neighborhood in

Lippmann, who was then the East Coast director of the organization MAZON – A Jewish Response to Hunger, invited ten friends for dinner to talk about a possible congregation in early 1993. The discussion continued over the following weeks and by the summer months, a once a month Sabbath dinner and a Saturday morning Torah study group were established. The congregation hired a teacher for the children the same year and for High Holy Days, Kolot welcomed 75 people.

The group started out on folding chairs in Kensington,

“I don’t believe in tickets for High Holy Days,” Rabbi Lippmann said. “When the issue comes up, and it does come up regularly as a way to raise money, I always say, ‘You can have tickets, but then you have to look for another rabbi.’ We do ask for contributions, though,” she added.

The other principle on which Kolot Chayeinu was built, is that the group eats first, and then prays. Rabbi Lippmann came up with this idea when she was, as a MAZON director, traveling and giving speeches in synagogues around the

“I joined with four other gay men and lesbians who’d been active in AIDS organizing in

For Wolfe, it was more important to be in a synagogue which welcomes all people than to be in a gay synagogue. “As a Jew, it was great to see a 70 year old woman from

Wolfe’s bar mitzvah ceremony was the first occasion when his parents met the parents of his lover of nine years, and his grandmother came to visit the home he shares with his lover.

Lisa Zbar, the 51 year old former Kolot Chayeinu President, a documentary film maker and a mother of two, grew up going to a reform synagogue, still felt left out of Judaism. She knew that she wanted a place where her husband, who is from the

When in 1995 a friend suggested Kolot, Zbar went to talk to the rabbi and immediately liked what she stood for. “I liked the idea that my children would know all kinds of adults – from single straight people to lesbian couples” she said. Even though Judaism had always spoken to her, Zbar never imagined that going to shul would mean so much to her. She wanted to be on the inside of “this Jewish thing,” she said, and wanted her children to be part of it too. Now she attends Shabbat services with her family. As the media is projecting fear and the country leans towards separatism, Zbar feels that Kolot and her home in which religious practices become cultural ones, are the right antidotes.

Kolot Chayeinu, which now has 230 due-paying members, is a progressive congregation not only because it welcomes all kinds of people, doesn’t charge for High Holy Day tickets and eats before prayer, but also because of what is stated in the group’s mission statement: doubt can be an act of faith.

“Kolot’s members have a wide range of opinions about

“A congregation like this lets people live their social agenda through their religion,” Professor Ari Goldman of Columbia School of Journalism and a former New York Times reporter covering religion, said. “It has been a Jewish tradition ever since the Enlightment to reject the constraints of the old and reinterpret them – being Jewish on ones own terms,” he added. This is especially true for those who came from a family where they were exposed to an orthodox variation of Judaism, Goldman said.

It is indeed true for Marcia Bodenstein, who, after the initial first service came back the next day to a service honoring the dead. “We all stood up and said the names of our dead. I said the name of my husband,” Bodenstein said. “Later, a man read the names of all countries that were at war. I felt that my heart was there too, not just my body. I did not look at my watch once. I felt that this is where I belong,” she added.

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Friday, October 20, 2006

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Sunday, September 03, 2006

Even if they lived outside of New York City at the time, passers by on Brooklyn streets felt their lives influenced by the terrorist attacks of 9/11. The six people I interviewed on a rainy day in late August almost five years after the attacks said that the possibility of another terrorist attack was on their minds. But they still felt safe in Fort Greene, the multicultural neighborhood of charming brownstones and abundance of greenery.

“My sister picked up smoking,” said Jeremy Wooster, 19, of Canarsie, when asked about 9/11 and its influence on his life. “She was looking for my brother and me that day and couldn’t find us. She didn’t know what else to do.”

Wooster, now a Bard College student, was attending a high school at the time of the attacks just a few blocks from The World Trade Center. His school was evacuated and after four days off, he and his schoolmates were for a month sharing a high school in Brooklyn. “The Brooklyn kids hated having us there. It was a bad experience. They should have given us more time off,” Wooster said. Now working at the Jewish Heritage Museum, he still visits Ground Zero often and is not happy about what he sees. “The small businesses are all gone. The places we used to go for lunch, they are all gone.”

“Tourists coming to Ground Zero really bother me,” Wooster added.

“It’s a huge graveyard really. Thousands of people are buried there and [tourists] come to take a picture. It angers me. I think it’s creepy.”

Sunny Kim, 30, of the Lower East Side, lived and went to school near Ground Zero in 2001. After September 11, she quit her job and moved out of the city. “There were other reasons for me to leave as well,” she said, smoking a cigarette outside a Laundromat. “I have never been to the site,” Now working as a teacher, Kim said. “I have people who come visit me and they say, ‘Hey, let’s go!’ and I just say, ‘Here is a map, you go.’ I can’t. I just can’t. And I am not a very emotional person.”

Meg Forbes, a retiree of Fort Greene heard about the first plane crash on the radio and thought that it was a “bad joke”. Later, when her sister called, she looked out the window and saw the smoke coming out of the tower. “I sat in my chair and I stayed in that chair until about 6 in the evening. I called everybody I knew,” she said.

Forbes attended a jazz concert at the World Trade Center the Friday before the attacks. “I was looking at all those pretty young girls and I thought to myself, wouldn’t it be nice to be this young, work in this beautiful building and make all this money. And look at it now, it’s all gone,” she said. When asked how 9/11 influenced her life, Forbes said, “Not a day goes by that I don’t think about it. I look out the window and see the empty space where the towers used to be. You wanna know how it influenced my life? I tell you. It made me miserable!”

Despite her strong emotions, Forbes is now able to travel around Downtown Manhattan. “I take the bus and look at the construction from the window. I hear there is an exhibit there now. I decided to go see it,” she said.

The majority of people interviewed expressed that they don’t feel safer seeing police with machine guns around the city and in subway stations. “I think the money spent on manhours of all those cops standing around chatting, could be better used,” Wooster said, adding that another attack on New York City would not surprise him.

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Friday, June 30, 2006

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

Orlando, one of its author’s best known works, is considered by some the longest love letter in the history of modern literature. Virginia Woolf, without hiding this fact, based the main character, the noble Orlando, on her lover Vita Sackville West. West’s pictures appear in the original print of the novel as illustrations of Orlando.

“He – for there could be no doubt of his sex, though the fashion of the time did something to disguise it – was in the act of slicing at the head of a Moor which swung from the rafters (13).” We meet Orlando, who is a man, in his early adulthood, when, as a noble man, he is introduced to the Queen and wins her attention, followed by many favors, because he is exceptionally beautiful. Just like in the first sentence cited above, Woolf gives frequent references to the body and the clothes in which the body is dressed, when she talks about the sex or in our modern term, gender of her characters.

Early in his life, Orlando is preoccupied with love of literature, especially poetry. Later, he encounters the pains of romantic love between young adults, when he falls in love with the daughter or niece of the Russian ambassador in London. At the beginning, Orlando does not know Sasha’s gender, but feels that he is attracted to her. “… a figure, which, whether boy’s or woman’s, for the loose tunic and trousers of the Russian fashion served to disguise the sex, filled him with the highest curiosity. The person, whatever the name or sex, was about middle height, very slenderly fashioned, and dressed entirely in oyster-coloured velvet, trimmed with some unfamiliar greenish-coloured fur (37).” In this part of the novel - which might be the only part where Woolf points this out directly - Orlando is scared that the person he finds highly attractive might be a male: “When the boy, for alas, a boy it must be – no woman could skate with such speed and vigour – swept almost on tiptoe past him, Orlando was ready to tear his hair with vexation that the person was of his own sex, and thus all embraces were out of the question (38).” Orlando, with this very simple end of the sentence, fully complies with the conservative tradition of his time and even though he is in despair about the possibility of Sasha being male, it does not cross his mind that love between two males could be acceptable as well.

Unlike Orlando, the character of Archduke Harry is one which does not think that loving another man is a cause not worth pursuing. When he fell in love with the portrait of Orlando, when Orlando was a man, the Archduke, of desperation, dressed as a woman to win Orlando’s love. Orlando flees England partially to get away from the Archdukes Harriet, who is Harry in disguise and they meet again only after Orlando became a woman herself, and came back to England. But Orlando had and has no interest in the Archduke or Archdukes, who as a woman, seemed rather grotesque in appearance to Orlando, suggesting that the Archduke did not perform the role of the female sex with much success. After Lady Orlando declines the Archduke’s marriage offer, he goes back to Romania with another woman.

Orlando undergoes his life altering transformation while being the Queen’s ambassador abroad. He is thirty years old, disappointed and hurt by both poetry and romantic love, lives his life as an important man of wealth when he falls asleep for seven days just to wake up as a woman.

“Orlando has become a woman – there is no denying it. But in every other respect, Orlando remained precisely as he had been. The change of sex, though it altered their future, did nothing whatsoever to alter their identity. Their faces remained, as their portraits prove, practically the same. His memory – but in future we must, for convention’s sake, say ‘her’ for ‘his’ and ‘she’ for ‘he’ – her memory then, went back through all the events of her past life without encountering any obstacle. Some slight haziness there may have been, as if a few dark drops had fallen into the clear pool of memory; certain things had become a little dimmed; but that was all.” (138)

Woolf uses the plural “they” to talk about Orlando in changing, as if she suggested that the person is now two people really, one male and one female, in the same body. Lady Orlando lived from this moment on not only with the face, but also with memories of Lord Orlando. With this turn, Woolf takes the opportunity to engage in social critique of the colonial English society of the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Orlando, as a woman, questions the society’s attitude towards women, his/her own attitudes towards women in the past and her/his actions based on these attitudes. Similarly to Lord Orlando when it came to poetry and romantic love, Lady Orlando will examine the society with an open mind, just to find that as a woman, more precisely, as an unmarried woman, her status is not comparable with that of the former Lord Orlando and other men of the society.

After her transformation from male to female, Orlando spends time in Turkey among a group of gypsies. Woolf gives her heroine a transitional time to come in terms with what has happened to her. The mental state and the transition itself is helped by clothing, which is gender neutral:

“With some of the guineas left from the sale of the tenth pearl of her string, Orlando had bought herself a complete outfit of such clothes as women then wore, and it was in the dress of a young Englishwoman of rank that she now sat on the deck of the Enamoured Lady. It is a strange fact, but a true one that up to this moment she had scarcely given her sex a thought. Perhaps the Turkish trousers, which she had hitherto worn had done something to distract her thought; and the gipsy women, except in one of two important particulars, differ very little from the gypsy men.” (153)

Nonetheless, it seems that Lady Orlando will never forget that she was a man for many years and she will meditate about the importance and the many functions of sexual identity, clothes and gender performance in social life and her own feelings about identity. Woolf gives Orlando the very unusual choice - at least philosophically - to which sex/gender she wants to belong. Knowing now both, Orlando finds herself wanting to be of none.

“And here it would seem from some ambiguity in her terms that she was censuring both sexes equally, as if she belonged to neither; and indeed, for the time being she seemed to vacillate; she was a man; she was a woman; she knew the secrets, shared the weaknesses or each. It was a most bewildering and whirligig state of mind to be in. The comfort of ignorance seemed utterly denied her. … Thus it is no great wonder if, as she pitted one sex against the other, and found each alternately full of the most deplorable infirmities, and was not sure to which she belonged – it was no great wonder that she was about to cry out that she would return to Turkey and become a gipsy again…” (158-159)

Orlando was, despite all confusion, very much conscious of her gender and started learning how to perform it correctly. To stress the point, Woolf uses the verb “act” when talking about performing gender roles. One of the first instances when an occasion for this arises is when Archduke Harry unmasks himself to her.

“Recalled thus suddenly to a consciousness of her sex, which she had completely forgotten, and of his, which was now remote enough to be equally upsetting, Orlando felt seized with faintness. … In short, they acted the parts of man and woman for ten minutes with great vigour and then fell into natural discourse.” (178-179)

Other changes in her actions and behavior due to change of sex/gender, as well as comparison of gender appropriate social norms of the times, are illustrated throughout the second half of the novel, like, for example here:

“Some way out of the difficulty there must be, she supposed, but she was still awkward in the arts of her sex, and as she could no longer knock a man over the head or run him through the body with a rapier, she could think of no better method than this.” (182)

In the following longer passage about Orlando’s gender identity Woolf at first states that men and women are different in appearance and in the way they relate to the outside world. However, in the paragraph following, she disagrees with the previous statement. Woolf seem here to strongly suggest that everybody has a part of a woman and a part of man in them and often it is clothes that give the only clear distinction to an outsider, as to what gender a person is. This is, in my opinion, the single most important passage in which Woolf very clearly explains her views on the perfomativity of gender.

“So, having now worn skirts for a considerable time, a certain change was visible in Orlando, which is to be found even in her face. If we compare the picture of Orlando as a man with that of Orlando as a woman we shall see that thought both are undoubtedly one and the same person, there are certain changes. The man has his hand free to size his sword; the woman must use hers to keep the satins from slipping from her shoulders. The man looks the world full in the face, as if it were made for his uses and fashioned to his liking. The woman takes a sidelong glance at it, full of subtlety, even suspicion. Had they both worn the same clothes, it is possible that their outlook might have been the same too.

“That is the view of some philosophers and wise ones, but on the whole, we incline to another. The difference between the sexes, is happily, one of great profoundity. Clothes are but a symbol of something hid deep beneath. It was a change in Orlando herself that dictated her choice of a woman’s dress and of a woman’s sex. And perhaps in this she was only expressing rather more openly than usual – openness indeed was the soul of her nature – something that happens to most people without being thus plainly expressed. For there again, we come to a dilemma. Different though the sexes are, they intermix. In every human being a vacillation from one sex to the other takes place, and often it is only the clothes that keeps the male of female likeness, while underneath the sex is the very opposite of what it is above. Of the complications and confusions which thus result every one has had experience; but here we leave the general question and note only the odd effect it had in the particular case of Orlando herself.

“For it was this mixture in her of man and woman, one being uppermost and then the other, that often gave her conduct an unexpected turn. The curious of her own sex would argue how, for example, if Orlando was a woman, did she never take more than ten minutes to dress? And were not her clothes chosen rather at random, and something worn rather shabby? And then they would say, still, she has none of the formality of a man, or a man’s love of power.” (188-189)

It is interesting that when Orlando was a man, at the beginning of the novel, it was clear that he was male. Now, after the change of sex, Orlando does not know who she is in terms of gender – although she knows that she is the same person she always was – and as Woolf puts it “cannot now be decided” what her gender is, even though, she clearly is performing the female gender role. He identity, it seems from this sentence, does not fully agree with the gender performance. Woolf seem to suggest that by achieving a certain age and acquiring certain experiences, Orlando transformed into a woman with the memories and consciousness of both male and female, Orlando’s gender must be ambiguous. As we mature and become more conscious of ourselves and the society which we live in, Woolf implies, we must realize that gender is not one or the other and set in stone.

“Whether, then, Orlando was most man or woman, it is difficult to say and cannot now be decided.” (190)

And to live like she felt on the inside, she used the outside to mirror her feelings, performing both sexes with equal ease. As she was both female and male, Orlando found herself changing sex/gender as frequently as she changed from a dress to a suit.

“Now she opened a cupboard in which hung still many of the clothes she had worn as a young man of fashion, and from among them she chose a black velvet suit richly trimmed with Venetian lace. It was a little out of fashion, indeed, but it fitted her to perfection and dressed in it she looked the very figure of a noble Lord.” (215)

And what is more, when she appeared in public dressed as a man, she was perceived and treated as a man.

“..for a man he was to her…” (216)

Orlando enjoys the advantages of changing identity with the clothes she is wearing, multiplying “pleasure of life” and “love of both sexes equally”, which is the only place the possibility of Orlando’s bisexuality is mentioned. Woolf also gives as a detailed account of Orlando’s day, in which she is a woman or a man, depending of the function she performs and the needs she want fulfill; and something in between or both, when in the privacy of her home, she is wearing a China robe, permissible for both sexes.

“… for her sex changed far more frequently than those who have worn only one se of clothing can conceive; nor can there be any doubt that she reaped a twofold harvest by this device; the pleasures of life were increased and its experiences multiplied. From the probity of breeches she turned to the seductiveness of petticoats and enjoyed the love of both sexes equally.

“So then one may sketch her spending her morning in a China robe of ambiguous gender among her books; then receiving a client of two (for she had many scores of suppliants) in the same garment; then she would take a turn in the garden and clip the nut trees – for which knee breeches were convenient; then she would change into a flowered taffeta which best suited a drive to Richmond and a proposal of marriage from some great nobleman; and so back again to town, where she would don a snuff-coloured gown like a lawyer’s and visit the courts to hear how her cases were doing – for her fortune was wasting hourly and the suits seemed no nearer consummation that they had been a hundred years ago; and so, finally, when night came, she would more often than not become a nobleman complete from head to toe and walk the streets in search of adventure.” (220-221)

Judith Butler writes in Undoing Gender: “Every time I try to write about the body the writing ends up being about language. This is not because I think that the body is reducible to language; it is not. Language emerges from the body, constituting an emission of sorts. The body is that upon which language falters, and the body carries its own signs, its own signifiers, in ways that remain largely unconscious (198).” When Virginia Woolf as a narrator of Orlando, meditates about the body, sex and gender identity of her hero/ine, at the very beginning, she writes about Orlando’s passion for poetry, literature, language. The only thing Orlando carries with her through centuries and on which she constantly works, as her body and the world around her changes, is the manuscript of The Oak Tree, the poem she started writing as a boy in 1586 and finished as a lady three hundred years later. But Woolf makes the point that despite the changes of the body and the language, the person of the writer is the same. “She had been a gloomy boy, in love with death, as boys are; and then she had been amorous and florid; and then she had been sprightly and satirical; and sometimes she had tried prose and sometimes she had tried the drama. Yet through all these changes she had remained, she reflected, fundamentally the same (237).”

What is the essence of the sameness which Orlando carries with her through centuries? Woolf does not give an unequivocal answer to this question and maybe there is none (Benhabib 343). Woolf avoids identifying Orlando’s sexuality as bisexual, homo- or heterosexual, leaving open a variety of possibilities for her heroine, who does adjust to societal norms as much as her nature allows, nevertheless knows in her heart that she is always the same person who she was before.

Who is Orlando? Neither a woman, nor a man or both; someone who changes gender identity with her clothes and exists without one when she feels like it? Is that possible? “Gender can be neither true nor false, neither real nor apparent, neither original nor derived. As credible bearers of those attributes, however, genders can also be rendered thoroughly and radically incredible (Gender Trouble 180).” Woolf does not tell us directly, who Orlando is and from all the clues she gives in the novel, one cannot conclude any one particular, rigid category Orlando could belong to as a gendered, sexual being. Even though some believe that “an ambiguously sexed, gendered, and racialized body is liberatory, because it ruptures dominant codes,” Orlando is far from liberated, trying to pass, get back her privileges and to fit in with the elite (Reed 31). And there is a big difference between culturally and legally sanctioned passing and the one that is not – Orlando could cross-dress and enjoy the love of both sexes, but even she could have not gotten away with wanting to “marry” a woman or wanting legally be a man to be able to marry a woman. “In some cases, cross-dressing may function to consolidate existing power relations, while in other, it may function to disrupt or displace power (Reed 32).” Reed also states that Orlando, the movie, but we might say that the same is true for the book, “examines the (visual) production of reality and questions the (non)correspondence between vision and knowledge in term of the ‘truths’ of sex and gender” (34). In the movie, Queen Elizabeth is played by a man (Quentin Crisp), though detected only by those who know this fact already, a song at the very beginning is song by the British techno-pop singer Jimmy Sommerville, and Orlando himself, is played by Tilda Swinton. Nonetheless, we couldn’t have imagined a better casting. The movie, as Reed points out, goes in great lengths to show how both genders, male and female are based on “manufacturing for public display” (34): “Men, including Orlando, dress and undress, don wigs, primp, and preen…Later, Orlando (as a woman) is fit into a very tight corset and secured with heavy string, her breasts crampingly bound and lifted. Such a juxtaposition present both masculinity and femininity each as elaborate productions of the body that require much effort, and actual work, to maintain (34).” By the end of the movie, the evolved Orlando has an androgynous look – she is a modern woman, who arrived at a state of sameness, as opposed to difference and the movie, as Reed points out, promotes this “naturalized androgyny” as it “denounces the polarities of masculine and feminine tout court without commentary about how these gendered positions – including the mediating term ‘androgyny’ (understood to be a ‘mixed’ and ‘neutral’ position between masculinity and femininity) – function politically and contextually (35).” Reed concludes her article by critiquing among other movies also Orlando for functioning within the dualistic thought of female/male, even if they present a space between the polar opposites, and are therefore “reinforcing existing social relations and cannot function as an ideal end point for a feminist politics” (36).

Gender is performance, Butler insists, a socially constructed one. “That gender reality is created through sustained social performances means that the very notions of an essential sex and a true or abiding masculinity or femininity are also constituted as part of the strategy that conceals gender’s performative character and the performative possibilities for proliferating gender configurations outside the restricting frames of masculinist domination and compulsory heterosexuality (Gender Trouble 180).” It is true that Woolf does not go outside of the heterosexual matrix. She lets Orlando the man, love a woman, even though a man is also in love with Orlando at the time. Lady Orlando, though, in the nineteenth century, realizes the need for a husband and marriage. She meets an unusual man, one that comes and goes according to how the wind blows and who suspects Orlando to be a man (252).

Orlando and Shelmerdine are queer, but what does this mean in terms of their gender? They both perform, for reasons stated below, their particular gender, by which they confirm that the only way to be – even be queer – is to accept the male/female binary. It is surprising, as Biddy Martin points out, that “feminists have reduced the possibilities of gender to just two, that is, men and women, gender has come to do the work of stabilizing and universalizing binary opposition at other levels, including male and female sexuality, the work that the assumption of biological sex differences once did” (104). But some feminists feel constrained by defining women only as other than men and welcomed queer theory as relief from this category. However, Martin argues that “lesbian and gay work fails at time to realize its potential for reconceptualizing the complexities of identity and social relations…” and as Orlando, some queer thinkers rebel “against the normalizing constraints of conventional femininity”, which can easily lead to invisibility (105). Martin emphasizes that “subordination of women does not follow simply from the failure to conform to convention, but also from the performance or embodiment of it” (106).

If Orlando wants to fit in the heterosexual middle class white English society, she must perform all aspects of her gender. Through her gender performance, she must provide the society with proof of her racial, social and national character.

Nationalism, heterosexism, classism, and racism all appear as a subject in Orlando. Feminists like Jaime Hovey are very sensitive to the fact that “Orlando critiques whiteness and heterosexuality ambivalently and unevenly; it uses racially and sexually ‘foreign’ subject to explore the ambiguous national and social identity of a queerly gendered white Englishwoman, excluded from the nation by her polymorphous sexuality” (398). Moreover, Hovey speculates, Woolf lets Orlando “pass as respectable and heterosexual, by displacing her transgressive sexuality onto racial others” (398) and Woolf uses humor and sarcasm to undermine the masculine imperialistic identity of Orlando, which, she insists in the first paragraph of the novel, is without a doubt.

Through gender and the fluidity of Orlando’s gender identity, Woolf ridicules the compulsory heterosexuality by, on the one hand, giving Orlando the desire for a husband, and describing it as an unhealthy neurotic mania, on the other. Orlando enters into her marriage for pragmatic reasons: establishing her national and class legitimacy and restoring her status, land, and titles (Hovey 400). It is the honesty with which Orlando and Shelmerdine share their cultural values, “homosexual, interracial, and cross-class sexual taste” that brings their gender in doubt (Hovey 402). It is in 1928, when women in England, regardless of marital status were granted the right to vote. In this context, Hovey implies, “Orlando slyly invites readers to unmask the ‘joking’ terms under which femininity is produced – as gender identities are often, if not always, produced – as both an adaptation and a contestation of the constraints of national, racial, and sexual inclusion” (403).

Identity is the effect of performance, if, as did Bell, we consider performance as Butler analyzed it in Gender Trouble (3). Thus, it is possible that Orlando, in her transitional period with the gypsies, was not a “woman” yet, and only when she took on the clothes and manners of the women of her time, could she take on the identity of a lady as well. Orlando makes herself visible as a woman, even though, she merely passes as one yet and passing “is a mobile encounter that is not to be collapsed into a becoming, since the one does not become the other: there are two identities mobilized, that which one ‘already has’ and the identity one takes on” (Bell 7). Orlando already had an identity – that of a noble man of privilege - and now must pass as a woman, if she wants to have a similar place in society. “The production of the effect of identity, the effect (and affect) of various models of affiliation, is an embodied process”, Bell writes (8) and we saw that Orlando had to not only learn to wear different clothes, use different gestures and apply different manners from her previous life, but she also had to adjust to a different historical moment with all its technological (the amount of books available), political, commercial, and social realities.

Works Cited

Bell, Vikki. “Perfomativity and Belonging.” Theory, Culture and Society 16

(1999): 1-10.

Benhabib, Seyla. “Sexual Difference and Collective Identities: The New Global

Constellation.” Signs 24 (1999): 335-361.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York:

Routledge, 1999.

Butler, Judith. Undoing gender. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Hovey, Jaime. “’Kissing a Negress in the Dark’: Englishness as a Masquerade

in Woolf’s Orlando.” PMLA 112 (1997): 393-404.

Martin, Biddy. “Sexualities without Genders and Other Queer utopias.” Diacritics 24

(1994): 104-121.

Reed, Lori. “Skin Cells: On the Limits of Gender-Bending and Bodily Transgression in

Film and Culture.” Educational Researcher 26 (1997): 30-36.

Woolf, Virginia. Orlando: A Biography. New York: Harc

Saturday, May 06, 2006

Friday, March 10, 2006

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

Sunday, January 15, 2006

“Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.” This is how Virginia Woolf’s novel, translated by Dezso Tandori and published in Budapest the year of my birth by Helikon, begins. And with these words begins one of the best movies of the past years, in my opinion, directed by Stephen Daldry based on a screenplay by David Hare. The movie is an adaptation of Michael Cunningham’s novel The Hours, inspired by Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway.

The movie is not filled with Mr. Cunningham’s presence. It is Virginia Woolf who emerges from every sentence, every uncovered taboo, and every metaphorical situation. We listen to Woolf’s words written and spoken. This movie is about a lot of things that happy people don’t want to know and the unhappy ones would like to forget about.

Three well known women – Mery Streep, Nicole Kidman, and Julianne Moore – play three very different women in the film. Streep is a New York-based editor in the 90s, who is called Mrs. Dalloway by her best friend, and whose first name is Clarissa, just like Mrs. Dalloway’s. Moore’s character is a housewife in 1950’s America, who is reading Woolf’s novel, and Kidman is the writer herself writing the novel Mrs. Dalloway.

Mrs. Dalloway is about one day in life of a higher class woman in London. We know her every thought, we know where she is going and also what others think of her. The writer in the movie argues that someone has to die in the novel so that the others will cherish life more. First, the heroine herself was supposed to die, but later the mentally unstable young man will kill himself, leaving his young wife behind. Woolf in her own life also chooses suicide, filling the pockets of her coat with stones and walking into the river, leaving war ridden Europe and her Jewish husband behind. But first, she finishes her novel.

Julianne Moore’s character, Laura Brown, lives like many wanted to live in the USA in the 1950’s: she has an ideal husband, a car, a beautiful son, a nice house, in a suburb and a second child on the way. Her husband brings fresh flowers every morning for his wife before he leaves for work. But in spite of all of this, Laura Brown is not happy. On this particular day, she takes her son to a neighbor and despite his protests, she leaves him there and goes to a hotel room to die. But before the water closes over her bed, just like over Virginia Woolf, she realizes: She cannot kill her unborn child. She promises herself, that as soon as the second child is born, she will leave her family and start her life over. And that is exactly what she does.

Meryl Streep’s character, Clarissa Vaughn, buys the flowers herself the morning of her best friend’s and ex-boyfriend’s celebratory party. Richard, Ed Harris, is a well-known poet, who at this point is very ill with AIDS and who calls Clarissa “Mrs. Dalloway”. “I stayed alive for you until now.” says Richard. “It’s time for you to let me go.” But Clarissa cannot let go, because, as she confesses to her daughter, the happiest moment of her life was with Richard. She thought from that moment on, that happiness would grow, but she was wrong – it all got worse. At the end of the day– after Richard jumps out of the window – Clarissa realizes that she was mistaken: her present life is not unhappy and empty. She kisses her partner of many years as an acknowledgement of this, but the partner has no idea what is going on.

The story ends with Laura Brown coming to her son, Richard’s, funeral and staying over at Clarissa’s. Clarissa meets the evil mother who abandoned her child, but who does not seem so evil at all. Every piece of the puzzle falls into place.

Michael Cunningham’s novel brings four basic issues, still taboos in the 21st century, to the spotlight.

The first is the question of suicide. How long must a person live if her/his life is only suffering? When has one the right to say: �I can’t take it anymore’ and die? Who are we living for? What is happiness? Whose life is it?

The second taboo is mental illness. Not everybody who is mentally unstable is crazy. There are those who are depressed or those who have schizophrenia, but our society has not learned to live with these people, and would like to lock them up, separate them from the rest of the population that is momentarily more mentally stable. Are we denying other realities than our own? And in connection with the first taboo – Which is harder: to be sick or to live with the sick person? How long is it a must to live with one’s illness?

The third taboo is the role of a classical housewife. Laura Brown cannot take the role of a housewife, she struggles to be a wife and mother, and she would rather die than keep trying. She chooses life, her own life, over her own death, which is only possible if she leaves her family after her second child is born. Her first born will never be able to cope with the fact that his mother did leave him in the end. But this is the only way Laura Brown can stay alive. Not all women are able to be wives and mothers.

The fourth is the issue of sexuality. It is known that Virginia Woolf was inspired by women – her novel Orlando has been called the longest love letter ever written, and was inspired by a woman. Laura Brown kisses her woman neighbor passionately and Clarissa lives with her female partner and daughter fathered by a sperm bank. Cunningham successfully implies that sexuality, despite what many want us to believe, was never one dimensional. Bisexuality and homosexuality are not inventions of the 20th century, only people can be openly what they are in a few modern cities and countries of today. Virginia Woolf could not talk openly about her love of other women, although she did it in subtle ways anyway. Laura Brown could not talk about the kiss, not even to the woman she kissed. But Clarissa Vaughn had the possibility and choice to live her life freely the way she wanted and her environment accepted her the way she really was.

It is possible that Virginia Woolf would not be too thrilled with Nicole Kidman’s sometimes glowing fake nose, but maybe she would be happy about this sensitive and brave movie, because Woolf was a brave woman. On the Oprah Show, Nicole Kidman has said that the nose, the clothes and the cigarettes helped her to form her interpretation of Virginia Woolf. Meryl Streep said on the same show, answering the question about coping with being a mother and a busy working actress, that she is very tired. She also said that she thinks the movie is about “despair and the desire to live.” I would add that it is also about despair and the desire to love.

By unfortunate promotional timing, the same time as The Hours, two other movies came out in the US. In Adaptation, Meryl Streep excels as a New York-based editor of The New Yorker. In Far From Heaven, Julianne Moore’s character is a housewife in the 1950’s suburbs. Since both movies and both actresses in them are brilliant, it is really only Nicole Kidman’s performance in The Hours that pleasantly surprised all, especially because many were skeptical about her being able to pull off Virginia Woolf in the first place.

The movie The Hours is like a silk scarf: it is soft, cold, but strong and beautiful, and it tears easily. It is made like this by the music, the lighting and the beauty of women; the unbearable heaviness of being, the unsolvable situations in life, the secrecy of emotions, shame, the art of pretence, falsehood and pose. There is no ideology in this movie – it is simply and honestly deeply human. And many will not like this. And many will.

When I first saw this movie, in December of 2002, the theatre was filled half by men and half by women. Not one eye stayed dry. They should have given all of us a packet of tissues with the ticket!

Miriam Molnar

(Published in Kalendarium, a traditional almanac, in Hungarian in Slovakia, 2003)

When I grow up, I want to be Charlie Kaufman. Or Aaron Sorkin, but that is a different story.

Before I started researching Charlie Kaufman, I imagined him as a short, chubby, bald guy running around the streets of New York or Los Angeles, nervously scribbling in his notebook with an evil smile under his nose. But I had to face the fact that he has lots of curly hair, is thin and maybe even tall (no reliable information about this so far). It is possible that he does run around the streets with a little notebook – no reliable information about this either.

I heard Charlie Kaufman’s name for the first time when I saw the movie Being John Malkovich (1999), for which he wrote the screenplay. The movie, in short, is about a poor New York puppeteer (John Cusack) who finds a job at the 13.5 floor of an office building, where he by accident discovers a tunnel leading to the actor John Malkovich’s (playing himself) mind. Those who brave the journey into the tunnel will be John Malkovich for 15 minutes and will afterwards be thrown out onto the side of the road off the New Jersey turnpike. The puppeteer shares his secret with a colleague (Catherine Keener) on whom he and his wife (an unrecognizably ugly Cameron Diaz) both have a huge crush, and who in return tortures both of them by only wanting to sleep with them when they are inside John Malkovich.

The movie is full of subtle humor. For example, when John Malkovich realizes that it might not be him who sometimes governs his own deeds and thoughts, he asks Charlie Sheen – of all people – to come to his apartment and give him advice. My favorite scene is when John Malkovich himself goes down the tunnel to his own mind and finds himself in a restaurant, where every guest is John Malkovich, every waiter and every item on the menu also. I guess that Jung would have imagined the subconscious of huge egos somewhat similarly.

The absurd does not end with the drama of the particular individuals: it turns out that there is a group of selected people who are traveling from body to body through time using the before mentioned secret tunnel and after taking control over the bodies, they live through centuries this way. (Kureishi’s book The Body has a similar theme.)

Charlie Kaufman wrote his alter ego into the movie Adaptation (2002) in the form of twin brothers. Nicholas Cage is both Charlie and Donald Kaufman, who are screenplay writers, both bald and overweight. Charlie has high standards, is not very successful, has low self-esteem and can only long for women. Donald is successful, overly self-assured and narcissistic and turns up for breakfast with several gorgeous women (the brothers live in the same house). Charlie is trying to write a screenplay from Susan Orlean’s book The Orchid Thief, with little success. Finally, he makes up his mind that he has to meet her and travels to New York, where only Donald is brave enough to actually talk to her (Meryl Streep). The movie and the adaptation Charlie is working on melt at this point and we realize only at the end that we are watching the adaptation itself, which, influenced by Donald, becomes full of violence, drugs and pornography.

Besides Nicholas Cage, Meryl Streep also excels, because her character also changes rapidly during the movie. Chris Cooper, who plays the orchid thief John, is a real jewel. He drives an old, rusty car, wears dirty clothes, has no front teeth (the story about loosing his teeth is a great one itself) and when he takes the writer for an orchid hunt, he gets lost in the wetlands. One of the most memorable scenes is when Meryl Streep’s character, in a somewhat elevated mood caused by an orchid based drug, calls the orchid thief and asks him to join her imitating a phone dial tone. Their success will be the source of enormous happiness.

Charlie Kaufman in this movie writes the way he lives: with difficulty. Donald lives the way he writes. Susan, the writer, writes about life, but does not live it. The life of the orchid thief John is a book that needs adaptation.

Charlie Kaufman’s newest movie, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), isn’t short of surprises either. I was a bit prejudiced seeing Jim Carrey’s name on the posters, but I was pleasantly surprised by his performance. Even more so was I pleased by Kate Winslet, who stole the movie playing a character that was more complex and rich in challenges.

We meet Joel (Jim Carrey) one morning on a train platform in Long Island, when he decides not to take the train to work, but to take the one that goes to Montauk. It is on this train that he meets Clementine (Kate Winslet). Their romance is going well, until one day Clementine decides that she wants to erase all memories of Joel from her brain. She visits the offices of Lacuna Inc. which happily obliges her wishes. It takes a night to do the procedure and Clementine no longer knows Joel the next day.

After Joel realizes what has happened, he decides to order the same procedure for himself and most of the movie happens while Joel’s memories of Clementine are being erased from his brain.

Because we see the story of Clementine and Joel unfold backwards (the freshest memories are being erased first), we see the whole picture only at the end of the movie. The film has very few characters and by the end of the movie the strings get tangled and it resembles a soap opera in which everybody takes advantage of everybody. Joel wants to stop the procedure while it is happening. But that is, of course, impossible. Here comes the most enjoyable part of the movie, in which Clementine and Joel try to hide from the eyes of the computer doing the erasure to save Joel’s memories of Clementine. The stage of his memories dissolves around them as they get destroyed and they try to hide among Joel’s childhood memories. We saw similar scenes in Being John Malkovich, when he wanders among his childhood memories, although these were mostly nightmares.

The real Charlie Kaufman was born in 1958 in New York state and studied film at New York University. In 1991, he moved from Minneapolis to Los Angeles, to be a writer on a sitcom. He lives in Pasadena, California with his wife and child. He does not give interviews and hates public appearances, although he was on The Charlie Rose Show and NPR in 2004.

Obviously, this man spends most of his time asking questions such as: Where is the human consciousness located? What is our identity comprised of? Who and what can influence our consciousness and identity? How do we know who we are and what we remember, and what motivates our feelings and deeds? The movies written by Charlie Kaufman address these questions. Nobody will be able fully to answer them in our life time, so we can look forward to many funny, surprising, intelligent screenplays coming from Kaufman’s kitchen.

(Published in Kalendarium, a traditional almanac, in Hungarian in Slovakia, 2005)

Monday, January 09, 2006

There was a big storm, hail and rain, we were told, but by the time we arrived, the sun was shining. Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Wide, spacious airport, where a little train takes the passengers with their luggage from one terminal to the other.

First we ate at the Wall Street deli thinking that we would be flying in an hour, but we were wrong. The crowds were growing, impatiently waiting to hear announcements from the loudspeaker, and also talking on their cell phones and eating. Everybody wanted to continue traveling immediately, but because of the delay, there was more and more chaos. Those who were so inclined started to argue with representatives of different airlines. Nobody knew when they would arrive at their final destination.

The tall black guy sitting next to me was past middle age. He talked loudly on his cell phone, laughed a lot and moved his baseball cap back and forth on his head. When he – after about an hour – left to get something to eat, a young woman sat in his place. She put her feet up on the chair across from us and took a book out of her bag. (She must have just bought the book, I thought. She wandered around the airport stores and then decided to buy this book with a nice pink cover.) But she was not reading, just watching the people around her and the big monitor, where names of those who already had a seat in the airplane were listed. (Of course, I could not see that far. Maybe I should be wearing glasses.) She wore sandals, the kind in which you have to put your big toe through a little strap so that they don’t fall off your foot. (She is going to be cold soon in these, I thought.)

And then the woman soldier came. She was black and seemed young. A medium-sized backpack was sitting on the floor next to her. She had earphones in both ears and as she sat down, she started reading a book. (Of course, I could not read the title of the book from where I was sitting. I really do need those glasses! Or do I have to take my binoculars everywhere with me?) First I thought about the soldiers that I saw on my way here. They were mostly young, but some of them looked around fifty, balding already, but that was not very visible, because they had their heads shaved. It was sad to see them, not that to see the young ones was not sad. The young woman soldier wore a uniform that would melt nicely into the country in Iraq or Afghanistan and the bottom of her pants was tucked into her boots.

And then I thought about where she was going. Or where she was coming from. And if she is going, because probably she is going, because she was in no hurry apparently, because it did not bother her, or at least not in any visible way, that the planes were late, so if she is going, then who is she leaving behind? Does she have a lover, or maybe a child, or children and if so, what are they feeling knowing that she left and maybe she will be not coming back? And her parents and siblings? I pictured birthday and Christmas photographs, her colleagues and friends who must miss her, must feel something.

And then I thought about why she joined the army in the first place. (The army here consists of volunteers. Why would anybody want to join? Except when you are dealing with someone like Hitler – that I could imagine. But if there were no armies at all, there would be no Hitlers either and no need for armies at all.) Maybe she wanted to have an education and this was her only option – the army pays the tuition, gives a stipend and health insurance. Maybe she really wanted to study badly and wanted to get out of her parent’s house. Maybe she gave birth early, because nobody told her how to be careful and she saw no other way to fix the rest of her life. And now she sits here at this airport and maybe she is on her way to Iraq and maybe there will be no rest of her life.

And then I thought about how two nights ago in Taos, New Mexico, Julia talked about a relative of hers who wants to join the army. I must have given her a strange look from beyond my red-wine-and-coke: (The Americans don’t know the red wine and coke combination and are always very surprised – coke with wine? Well, what a strange idea of these Central Europeans!) To the army? Is this guy insane? And of course, I should not have given the look because Julia lowered her eyes and said that the guy is not insane, it’s only that he does not know what to do with himself. His mother cared for him for all these years, studied with him for every test. But he will be eighteen and his mother cannot go to college with him, can she? If they would accept him. And she cannot go to work with him every day, can she? And the guy cannot stay at any job long enough and he feels uncomfortable in this society which accepts only the successful ones, even though his parents did not raise him this way and stressed that what society expects is not what really matters. But he thinks the army will put him into place. Because there he will have no choice.

Especially, if he gets shot dead somewhere, I thought, though I did not say this, because I saw how hard the whole thing was for Julia. The guy’s sister is a big anti-war activist in their high school, and the whole joining the army thing is a big secret. And of course I was just sitting there mute, eating my delicious vegetable rice and tried not to think about how this guy will also become just a killing machine, if he survives the brain washing. Or he will have a nervous break down and will be haunted by nightmares, because how can anyone survive with a healthy psyche what one sees in war? And feels? And knowing that there is someone out there who wants to shoot me, who hates me only because I am wearing this uniform? And I thought, while the rest of the table was exchanging small talk pleasantries, that someone should take this guy to the nearest veteran’s hospital. He should work there for a month and see how it is, when one does not have a leg or an arm or has burns all over his body or is a bit crazy. Or someone should take him to where the dead are arriving in their coffins and he could work there too and see how the families receive the coffins, and the mothers are breaking down and the fathers are losing it as they cry. Someone should show this guy what it means to be in a war, which is not a video game, which has lasting consequences.

And then I thought about a different conversation with another woman in which she was telling us how one of her nephews came back from the war unexpectedly and how the family is not talking about what happened to him. Maybe he had a nervous break down, said the woman, but we don’t know, because nobody says anything and nobody asks anything, although all of them are worried, because he was a nice guy before he went to Afghanistan, and who knows what is going to happen to him now. And you could feel something behind this woman’s words, something about how the soul of this guy, who was a nice guy, rebelled and could not take it anymore and so it broke down, because this kind of experience is not for nice guys. New Mexico is one of the poorer states and this suits the army because the poor enlist more easily than the rest. In the meantime, I thought about a guy who I talked to many years ago in Budapest and who fought on the side of the Soviets in Afghanistan against the Americans, and he said with vehemence that only those who wanted to kill went there. And he went there to be adventurous and because he wanted to kill a man and he paid for it dearly and will never go to war or would want to be in the army again.

And then I thought about the young college student who wrote in her paper that she hopes all white people will burn in hell for what they did to the black people in this country. And that when she was traveling on the bus, she did not give up her seat to the old white lady who was standing and even felt like punching the little old lady in the face. This young college student is studying to be a police officer. And maybe in just a little time she will have a real gun in her hands and I hope I will never meet her on the street at night, because who knows how that would end.

And then I thought that the woman soldier, who is just sitting here quietly, is black too, but she does not seem to be angry, while it is very probable that her ancestors were dragged here from Africa by some ugly white man to be slaves for decades and decades for other white people. No wonder that blacks are angry when they realize that they cannot go to college or get good jobs, because it was the white men who became rich as a result of their ancestor’s work, and not them. No wonder.

And then I thought about what could be in her backpack. What does one take to a place from which one may not return? Not much fits into a medium-sized bag. What would I take? A notebook, because there is no electricity in the desert, a laptop would not be useful. Pens and pencils and pictures. And my camera, because what if I survive, and if not, maybe someone would find it and send it to my family. Body lotion for sure, and sunglasses and a hat, but that they would give us, I guess…Interesting, I can’t think of many necessary things.

And then I thought that this woman at the airport, who is also being watched by others, did not isolate herself from the environment by accident with her earphones and book. I have decided by that time that if she looks up, I will smile at her, but what I really wanted is not to smile, but to get up and hug her and say something that would make her feel good. Or to save her, to take her with me so she would not have to go to the war or even just to say to her that I will be her friend, if she needs one. We could talk and email and I would send her packages with M&Ms and milk chocolate. She could tell me her fears and anxieties, which she cannot tell her family, because they are already worried, they have a strong bond and we don’t have a bond at all. But the woman did not look in my direction and I did not go up to her and did not hug her and did not say anything.

The boyfriend of the girl sitting next to me arrived. He was also wearing those sandals. He offered his jacket to the girl, who was cold, of course. They talked. First about the plane and the delay, but later about people. Near the counter from where the plane to New York would be leaving, two passengers from Damascus were screaming at Delta employees. The man’s face was red and his voice was given some support by his fist in the air. His wife was standing next to him and nodding vehemently. Eventually, hours later, we saw him boarding the plane alone and we thought that maybe she was not his wife at all, or he left her in Atlanta, or she left him in this big mess and maybe she would never ever go back to him because after waiting for twelve hours for their connecting flight he still couldn’t make it to leave!

But when the Egyptian taxi driver, who picked us up at JFK, was showing us the picture of his Irish wife and nine-year-old son, instead of getting us home as quickly and safely as possible after this long journey, I still thought of that young black woman soldier. Where could she be and what could she be doing? And I thought about how this taxi driver, whose English was very bad and who had a degree in bio-engineering, was very lucky to be able to go home to Queens to his wife and son and how many in Iraq and Afghanistan are not able to do that. And that the soldier woman will be waking up or going to sleep to the sound of bombs going off and cars being blown up and shooting – and why all of this? Because some insane men think that their god is better than the god of the others? And is this 2005 or are we still in the middle ages? Because it is dark, our age, however they will call it hundreds of years from now.

Written in May 2005 in New York City

(Published in Kalendarium, a traditional almanac in Hungarian in Slovakia, for the year 2006.)